Amended Nevada Senate Bill 292 Continues to Place Impossible Burdens on Minor Political Parties – Article by Gennady Stolyarov II

Gennady Stolyarov II

The anti-minor-party Nevada Senate Bill 292 has advanced out of the Senate Committee on Legislative Operations and Elections on a party-line vote (3 Democrats in favor, 2 Republicans opposed). An amendment from the bill sponsor was included in the bill; Amendment No. 230 is an incremental improvement but maintains essentially insurmountable barriers for minor political parties. While the amended bill no longer raises the petition-signature threshold from 1% to 2% of the Nevada voters who voted in the last election, it does still seek to impose an impossible “equal distribution” requirement for the petition signatures and also moves the deadline for submitting petition signatures from the current third Friday in June to June 1.

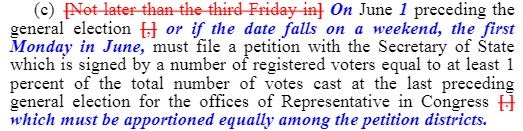

Section 2 of SB292 is the most onerous for minor political parties. The provisions further limiting ballot access, relative to the already significant requirements, are found in the new language that the bill sponsor, Nevada Senator and former Nevada Democratic Party Chair Roberta Lange, wishes to insert in NRS 293.1715(2)(c), stating that to qualify for ballot access, a minor political party must:

(New proposed wording above is in bold blue italics, wording proposed to be deleted is in red strikethrough.)

While various other problems exist with SB292, particularly with the concept of straight-ticket, party-line voting – which aims to absolve voters of the essential responsibility to study individual candidates and their stances on the issues – the present commentary will focus on the most egregious flaws with Section 2 of the bill: requiring that the petition signatures be “apportioned equally among the petition districts” and moving the deadline for submitting petition signatures to June 1 preceding the general election.

The bill sponsor appears to be of the impression that removing the previously proposed doubling of the number of petition signatures required would alleviate the most visible added burden on minor political parties. Yet the remaining requirement of equal apportionment is actually far more burdensome and more insidiously so. It requires several more steps in one’s thought process to discern the burden – hence, the bill proponents may believe it to be a viable option to insert such a provision without significant portions of the public noticing or voicing their objections. Therefore, it is important to elucidate the immense problems with the “equal apportionment” criterion.

Nevada has four petition districts, corresponding to the U.S. Congressional Districts. The 3rd Congressional District is the most populous, with a population of 857,197 as of 2019. All three of the other Congressional Districts have populations below 800,000. Suppose that a minor political party were spectacularly successful in gathering petition signatures and managed to collect them from the entire population of registered voters in the 3rd Congressional District. (For this example, we will assume that the proportion of registered voters to the general population is the same in each Congressional District.) The very fact that this minor political party could accomplish such a feat would render it impossible for that party to qualify for ballot access, because the other petition districts simply do not have enough registered voters to match the number of signatures gathered from the 3rd Congressional District in that case.

Moreover, the “equal apportionment” requirement renders it almost effortless for a major party to challenge petitions submitted by minor parties, simply by counting the signatures from each district and noting any difference whatsoever in the numbers of signatures, even if the difference is literally one signature! Even if the total number of signatures is well above 1 percent of the registered voters statewide, if the number of signatures gathered in one petition district were 10,000, and the number of signatures gathered in another petition district were 10,001, that also, by itself, would be sufficient to technically fall out of compliance with the requirement of “equal apportionment”. Note that the text of the amended NRS 293.1715(2)(c) would not allow any room for deviation from a strictly “equal” apportionment. There is no mention of a possibility for the apportionment to be made “approximately equal” or “reasonably equal” or “equal within a tolerance of X%”; the text would mandate strict equality of petition signatures by district, and it appears to me that the Democratic Party proponents of the bill did this intentionally to be able to disqualify any minor party’s petition on a technicality. Given that different circulators of petitions are likely to operate in different petition districts, it is virtually certain that different numbers of signatures will be gathered by each team of circulators. This is so because precise coordination at the level that would be needed to achieve exactly equal numbers of signatures among all four districts and to stop gathering signatures in a perfectly choreographed fashion once such equal numbers were attained, would be essentially impossible to achieve.

Moreover, suppose a minor political party represented a set of positions that resonated to a greater extent with a particular segment of the Nevada population – for instance, young urban professionals, ranchers, miners, university students, residents of rural areas. Each petition district has considerably different proportions of these demographics than the other. For instance, the 1st Congressional District is 99.90% urban, so a hypothetical party that focused on representing the interests of ranchers or rural residents would find quite limited support there. Some city dwellers might, of course, sign a petition for such a party’s ballot access on principle, because they support inclusion of all political parties on the ballot; however, from a sheer probabilistic standpoint, the number of such people would be fewer than the number of people in rural areas who would be willing to sign that party’s petition. Even if the hypothetical party representing rural interests only intended to run candidates in rural areas, it would still need to receive an equal number of signatures from each urban-heavy petition district in order to qualify for the ballot. Therefore, regional parties or parties representing specific constituencies would essentially be permanently barred from ballot access by the “equal apportionment” requirement.

Because of the additional coordination required to even attempt to gather petition signatures “equally” by petition district, as contrasted with simply trying to gather as many signatures as possible, one would expect that the petitioning effort would be more time-consuming than previously. However, Section 2 of SB292 reduces the available time for a minor party to comply with the added burdens, thereby further lowering the probability of successfully meeting all of the requirements.

Moreover, the United States District Court for the District of Nevada already struck down an even less burdensome deadline of June 10; this occurred when the Judge in the case of Lenora B. Fulani et al. v. Cheryl A. Lau, Secretary of State (“Fulani v. Lau” – Case CV-N-92-535-ECR) issued a preliminary injunction on October 1, 1992, to require the State of Nevada to include Lenora Fulani and other independent and minor-party candidates on the ballot despite those candidates not having been able to gather the required number of signatures by June 10 of that year. In issuing the preliminary injunction (which effectively decided the case, since the election took place in November of the same year), the Judge wrote “that plaintiffs have shown likely success on the merits, that the balance of hardships tips in their favor and that they will suffer irreparable injury if their names are not put on the 1992 ballot” (Fulani v. Lau, p. 14). The Judge explained that

The character and magnitude of plaintiffs[‘] injury caused by the June 10 filing deadline shows a burden on their First and Fourteenth Amendment rights. The deadline burdens the rights of nonmajor parties[‘] candidates by excluding late[-]forming parties and forcing candidates to circulate petitions before most of the voting population has thought about the elections. Although this date is not as early as others which have been struck down as unconstitutional, most other states require the petitions be submitted several months later. Also, no evidence suggests that candidates who lack an established national affiliation are easily able to access the ballot. (Fulani v. Lau, p. 11)

If the United States District Court found that a June 10 petition-filing deadline is burdensome to non-major parties’ First and Fourteenth Amendment rights, then, logically, a June 1 deadline would be even more burdensome. Such a deadline would indeed serve to thwart any but the most amply funded minor political parties, if those parties choose to begin gathering the signatures extremely early in the year, whereas new minor parties, as well as minor parties that rely largely or exclusively on volunteer efforts and grass-roots organizing, would find themselves hobbled by lack of time. SB292 is seeking to institute in Nevada law a deadline more stringent than the one which the District Court has already overturned.

There is still time to express opposition to Senate Bill 292, particularly to the requirement that petition signatures be equally apportioned and the earlier June 1 deadline for submitting such signatures. SB292 is already one of the most actively commented on and least popular bills of the 2021 Legislative Session, with 209 public opinions expressed in opposition and only 4 in favor. You can submit your opinion in opposition to SB292 here and also e-mail the Senate Committee on Finance, where SB292 will be headed next, at SenFIN@sen.state.nv.us, as well as e-mail the Assembly Committee on Legislative Operations and Elections at AsmLOE@asm.state.nv.us. The Assembly Committee on Legislative Operations and Elections would be the committee where SB292 would be heard if it were to pass in the Senate. Please express your concerns civilly and politely but make it clear that you do not agree with any attempts to further limit minor-party ballot access. Also, please spread this article to as many constituencies as possible! People of nearly all political persuasions should be able to agree on the importance of voter choice and to abhor the injustice of intentionally restricting candidates and parties from even being available for voters to consider.

Even the current ballot-access thresholds in Nevada are unduly stringent; the last time a minor political party qualified for the ballot through petitioning in Nevada was in 2011, when the Americans Elect organization was able to submit the required number of signatures. It is time to pursue reforms in the opposite direction from Section 2 of SB292; it is time to repeal all petitioning requirements for ballot access and allow voters the choice of any candidate or party whom they wish to support. At minimum, it is essential to oppose the placement of any further obstacles along the path to ballot access. All provisions of SB292 related to minor political parties should be amended out of the bill upon further revision. Please add your voice to this important effort to preserve electoral choice and to oppose one major party’s efforts to monopolize Nevada elections.

Gennady Stolyarov II is the Chairman of the United States Transhumanist Party.